The backbone of cross border transactions: correspondent banking

A few weeks ago, while preparing my 10k analysis for Adyen, I came across a very interesting McKinsey report on Payments and stumbled into the following table on cross-border transfer flows and revenues:

What really surprised me, even more than the huge revenue chuck of the B2B segment, was the disproportion between consumer and business segments and, at the same time, the opposite trend in startups. Here is why, I thought, I see so many startups trying to build in the C2C payments space, even though in B2B there is a 5x bigger opportunity. Trying to get to the bottom of this, I started investigating, together with some fellow guilders of the Fintech Product guild, on the fundamental piece of infrastructure that powers these transactions: correspondent banking.

The goal of this post is to go through the process of sending money through correspondent banking corridors and to look at how new technologies might change it all.

What is correspondent banking?

Correspondent banking is defined as “an arrangement under which one bank (correspondent) holds deposits owned by other banks (respondents) and provides payment and other services to them.

In order to fully get the concept and the implications of this banking model, it is very useful to contextualize it in the wider bank transfer ecosystem.

Sending money through your bank to somebody else is a fairly standardized process nowadays: based on the recipient destination you might have to fill in in your app few or less fields - but ultimately the complexity is totally abstracted away from the bank user. In reality, sending money to somebody with an account in your bank or in your country (economic area) or in the rest of the world, it’s a very different process.

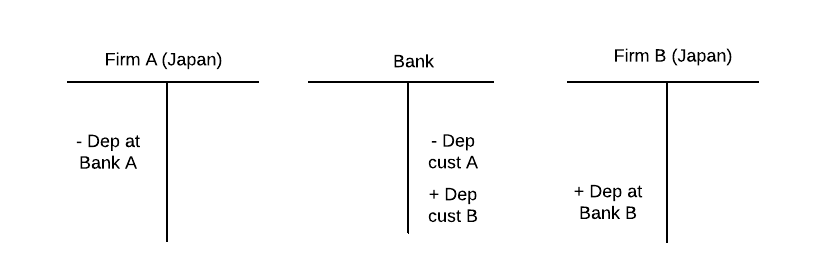

If your recipient is in your bank - the money will be transferred in a matter of seconds, it’s just a change in the liability side for your bank.

If your recipient is in your same country or economic area - the transfer will take some more time but it will essentially be guaranteed by a ‘national’ payment scheme (SEPA).

If your recipient is in another part of the world, things get trickier: unless there is a specific agreement between your bank and the recipient bank, there is no common scheme that is connecting them, because a common global scheme that connects all the banks in the world doesn’t really exist. To send your money to your destination, your bank will have to be part of a global network that regulates correspondent banking (the SWIFT network) and a correspondent bank will have to act as an intermediary.

As shown in my example, It is possible that more than one correspondent bank will be necessary to get to the destination, but due to the hierarchical structure of the SWIFT network, the delivery of the payment to the counterpart is essentially guaranteed.

PS: Just to be clear, the financial mechanics of this transaction are more complex than a simple money transfer, because the correspondent bank will also provide currency exchange service, thus it will have to hedge the currency transaction in some form, but this complexity is external to the pure corresponding banking process and thus I will not explore it in this post.

SWIFT, the most critical telecommunication company in the world

As briefly anticipated above, the core of the correspondent banking model is represented by SWIFT, the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication.

SWIFT was created in the 1970s by a consortium of banks, that still owns the company, to facilitate cross-border banking interactions. Since the 70s, SWIFT has been the essential monopolist in cross-border payment infrastructure.

As suggested by the name, SWIFT is a telecommunication company that supports financial applications: it essentially delivers billions of messages every year to make the cross-border monetary flow happen. An important thing to note is that SWIFT is a pure telecommunication company: it can deliver your messages to anyone fast and securely, however, it doesn’t provide the legal framework for settlement that banks often establish on 121 basis.

The volume of transactions processed is staggering:

The data around the monetary volumes of these transactions is not clearly presented but numerous sources reports around multiple hundreds of $ trillion per day.

Going back to the example presented above, how does SWIFT concretely work to move money?

SWIFT doesn’t physically move money, and the transactions are not settled at SWIFT level or on SWIFT balance sheet. SWIFT is a telecommunication company that propagates messages containing financial transactions’ details between origination and destination. This is done essentially through two methods: serial or cover.

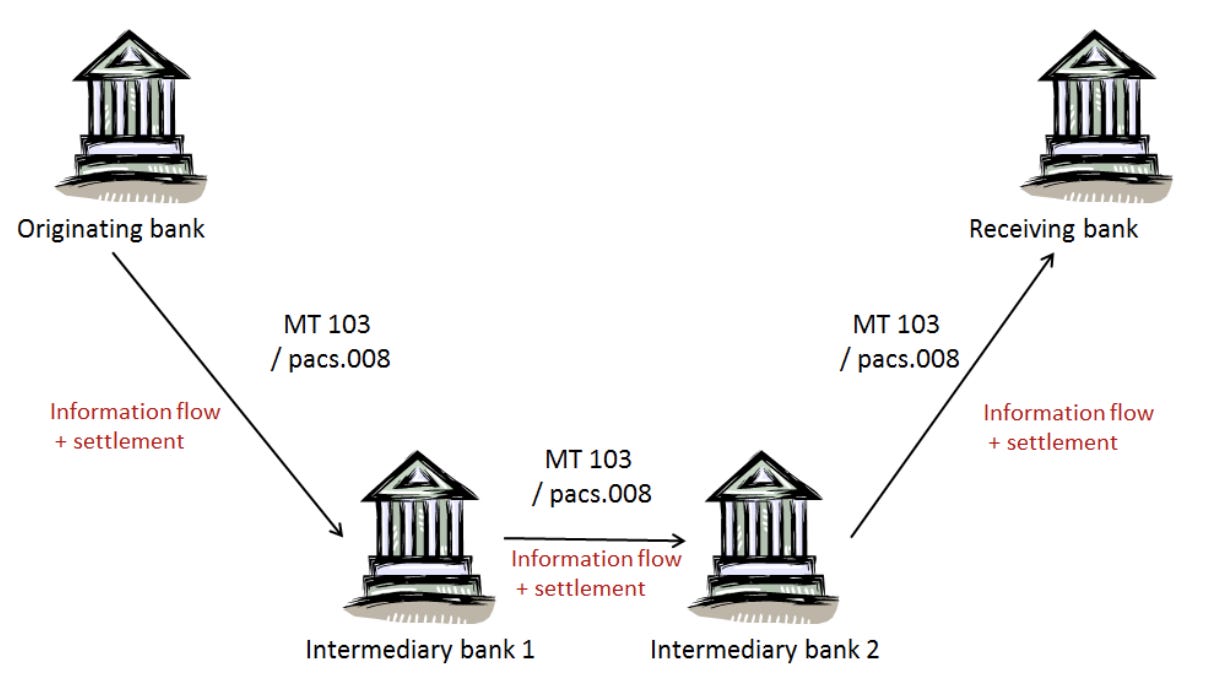

The Serial method is simply a chain of single transactions between each bank in the chain with each bank having an account at the other bank. The payment information and the settlement instruction travel together in the MT 103 message (the most common SWIFT standard).

Correspondent banking - Serial method [Source: BIS]

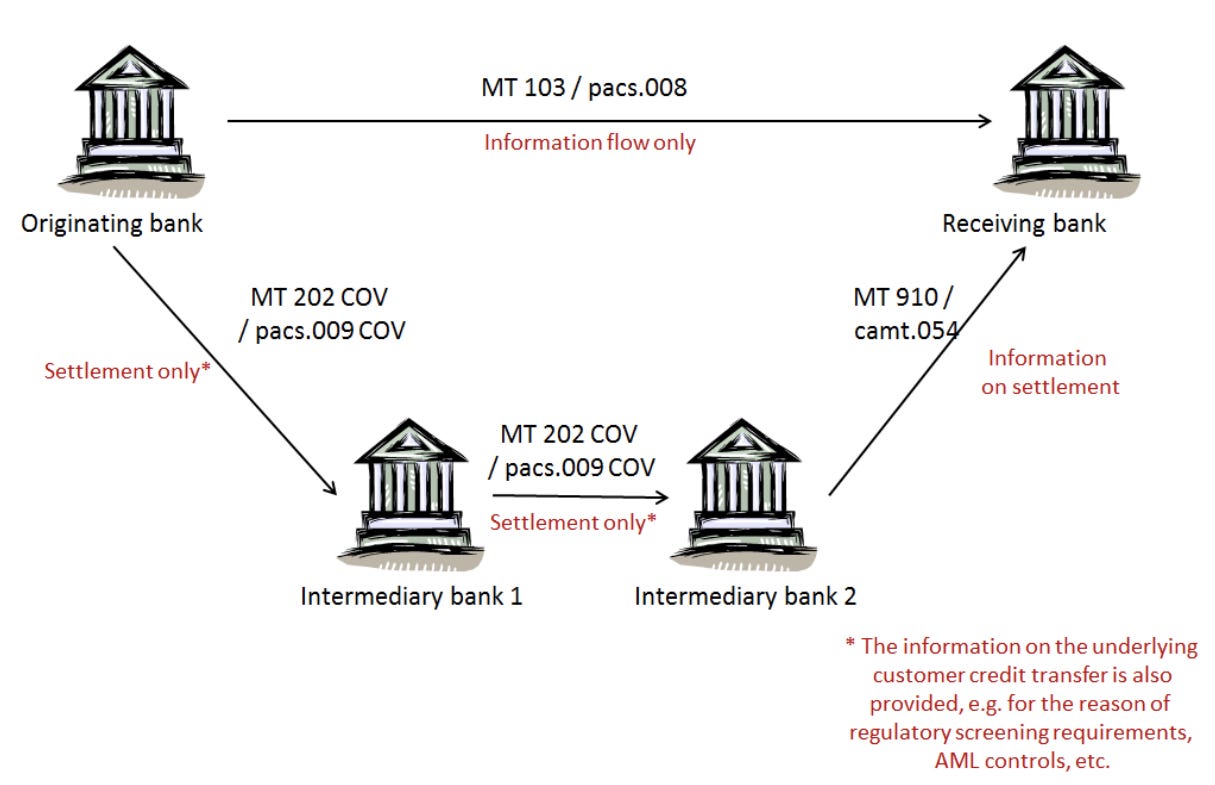

The Cover method decouples the settlement from the payment information. On one side, the MT 103 with the payment information is sent directly through the SWIFT network from the originating bank to the receiving bank; whereas the settlement instruction (the cover payment) is sent via intermediary banks through the path of direct correspondent banking relationships - through an MT 202 message.

Correspondent banking - Cover method [Source: BIS]

The cover method is theoretically cheaper, because banks do not take any additional fees from processing an MT 202 message, while they do it for an MT 103. In reality there are other cost elements involved in the equation to be factored in.

The cover method is also faster because the destination bank is aware of the incoming message and can investigate if the payment is stuck somewhere upstream, something that isn’t possible for the serial method, where the destination bank becomes aware of incoming transactions only when they are at destination.

The next step in correspondent banking

Over the last decades multiple attempts of disintermediating have taken place: multiple players have attacked one by one multiple use cases that were once served by SWIFT, but the Brussels-based consortium remains the core infrastructure of the vast majority of the cross-border payment volumes.

The latest attack is mainly coming from Ripple, a company that built a blockchain based technology which claims to be cheaper and more efficient than SWIFT.

Due to the nature of the problem, I believe that blockchain technology can be extremely promising in the B2B cross border space, but due to various reasons, network effect being the first one, so far nobody has not cracked the SWIFT domination.

Anyhow, the future of SWIFT and correspondent banking is a very fascinating but also very articulated topic and it definitely deserves a stand-alone post. Stay tuned.

Thanks to my friend (and former SWIFT employee) Alex Eliseev for his kind and extremely valuable review of this post.

Resources

https://www2.swift.com/knowledgecentre/publications/us1m_20190719/2.0?topic=mt103-guidelines.htm

https://www.swift.com/sites/default/files/documents/swift_annual_review_2019.pdf

https://efinancemanagement.com/international-financial-management/correspondent-banking

https://cib.db.com/insights-and-initiatives/flow/correspondent-banking.htm

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/home/pdf/research/Working_Paper_412.pdf

https://cib.db.com/insights-and-initiatives/flow/correspondent-banking.htm